Seven Experimental Classics To Be Preserved Through Avant-Garde Masters Grants

|

|

Cathy Cook’s The Match That Started My Fire (1992) will be preserved by the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

|

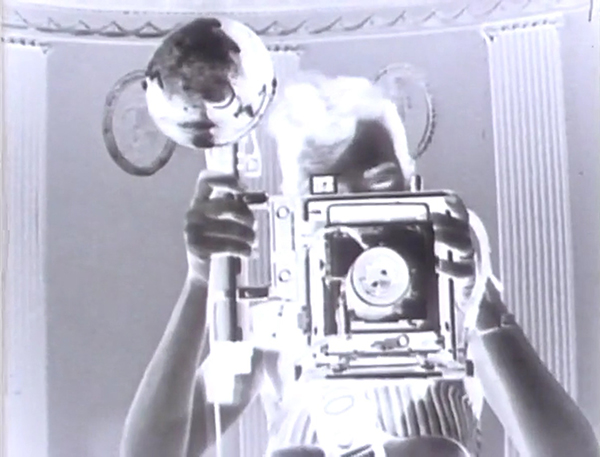

During his short life Ron Rice (1935–64) completed only three films. Senseless (1962), his second and least seen work, arose from an attempt to film the counterculture in Venice, California, and a utopian commune in Mexico. Rice combined home movie–style footage, street photography, landscapes shot from moving vehicles, and images from a bullfight in Acapulco. The result, anti-narrative in structure but formalist in its montage, was “close to being a film equivalent of On the Road,” according to avant-garde film scholar David E. James. Anthology Film Archives will oversee the preservation.

The State University of New York at Binghamton will preserve Ken Jacobs’s Binghamton, My India (1969), an experimental documentation of his first year of teaching at the college. Jacobs was hired after students petitioned the administration; alongside Larry Gottheim he organized the SUNY system’s first department of cinema. In Jacobs’s words, Binghamton, My India “said something necessary at the time: the numinous is everywhere, even upstate Rust Belt Binghamton. The light was perfect, [the] students brilliant.”

Cathy Cook, Associate Professor in the Cinematic Arts at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, has made films since 1982. The Match That Started My Fire (1992), produced between the second and third waves of feminism, uses a montage of educational and industrial films to explore female sexuality and to illustrate 20 short candid stories of sexual discovery related by a diverse collection of subjects. George Kuchar, whose videos Cook had performed in, has a cameo. The film won the Best of Festival award at the 30th Ann Arbor Film Festival and will be preserved by the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive will preserve four works by Roger Jacoby (1945–85), a key transitional figure between the pre- and post-liberation eras of gay experimental filmmaking. Dream Sphinx Opera (1973) and L’Amico Fried’s Glamorous Friends (1976) demonstrate Jacoby’s use of hand-processing to manipulate film emulsion to create abstract images. The former uses found footage from costume dramas and stag films to send up heterosexual romance, while the latter approximates an Abstract Expressionist painting in motion. Both feature Jacoby’s muses Sally Dixon, the Carnegie Museum of Art’s Film Curator, and Ondine (Robert Olivo), a veteran of several Andy Warhol films. After being diagnosed with HIV, Jacoby moved to Seattle, where his films took on a more journalistic and personal style. How to Be a Homosexual Part I (1980) turns the camera on members of his community, including his sister and mother, a deaf friend, and a gay couple in the Gay Activist Alliance. How to Be a Homosexual Part II (1982) focuses on Jacoby himself, seen tending to his ailing body, and his partner Jim Hubbard.

Over the course of 19 years the Avant-Garde Masters Grant program, created by The Film Foundation and the NFPF, has saved 207 films significant to the development of the avant-garde in America. Funding is provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. The grants have preserved works by 81 artists, including Kenneth Anger, Shirley Clarke, Bruce Conner, Joseph Cornell, Oskar Fischinger, Hollis Frampton, Barbara Hammer, Marjorie Keller, George and Mike Kuchar, Carolee Schneemann, and Stan VanDerBeek.